Jon Larsen, PE - CNU Utah Board Chair

In April of 2017 a junior high student was hit and killed in Syracuse, Utah while crossing the street at a crosswalk in front of his junior high school. This story hits home to me for two reasons. I have a son this same age who I absolutely adore, and I can’t imagine how bad it would hurt to lose him, especially in such a senseless way. Second, I believe that my profession (traffic engineering) has failed this young man, his family, his school, his community, and hundreds like them throughout this state and country. There’s no other way to put it. Failure. Epic Failure. Someday as a profession and as a society we will stop giving lip service to the concept of “Zero Fatalities” and make real change. I’m hoping it’s sooner than later.

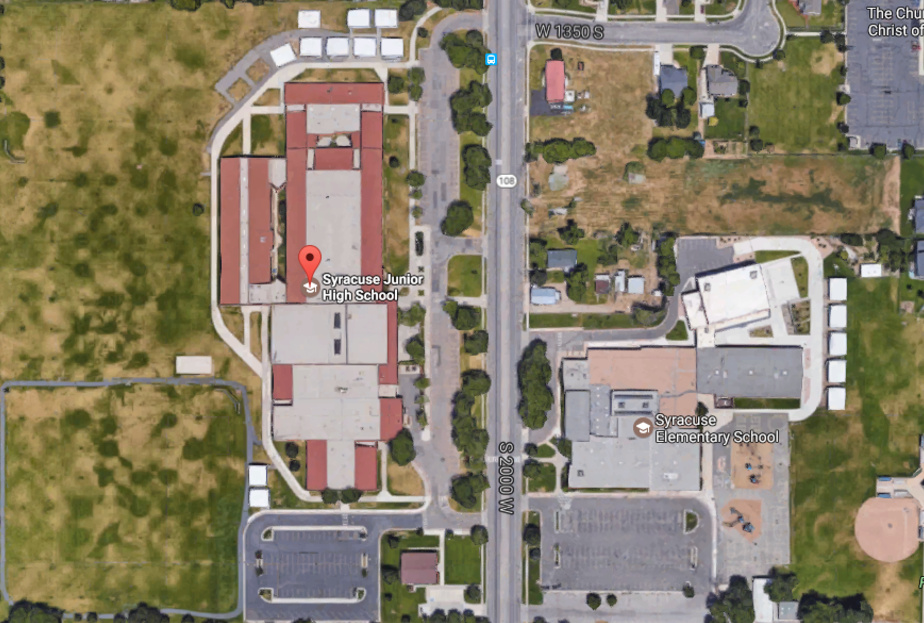

Let’s take a look at specifically how we failed in this situation. There is an elementary school and a junior high school across the street from each other. This street should be one of the safest streets in the city. But it isn’t.

Source: Google Maps

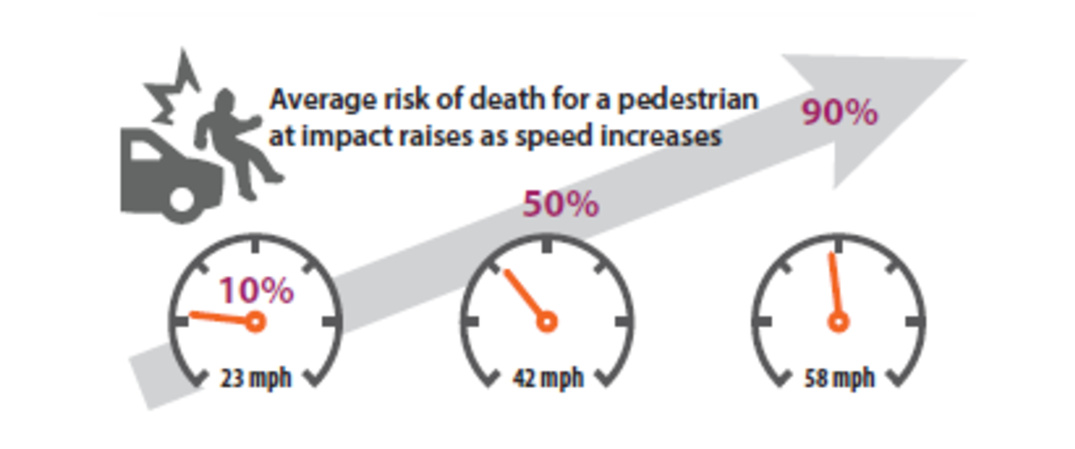

A quick physics lesson explains why this street is so unsafe. The force of impact from a car increases exponentially with speed. This means that doubling the speed quadruples the force of the impact. The statistics bear this out. When it comes to severity of impact, a 40 mph street is about 5 times more deadly than at 20 mph street.

Source: FHWA

Considering that kids are coming and going from these schools throughout the day due to extracurricular activities, etc., you would think that the permanent speed limit would be 20 mph. Maybe 25 mph. Nope. The speed limit on this street is 40 mph. Refer again to the chart as to why 40 mph is so much worse than 20 mph.

It gets worse. Some years ago, for my master’s project, I looked at the impact of speed limits on the speed that people actually drive. I learned that drivers don’t choose their speed based on the posted speed limit. Drivers choose their speed (without really even thinking about it) based on the design of the street. The street separating these two schools in Syracuse was designed for speed, which means it was designed to kill.

No one thought of it that way, no one meant for it to be that way. But that’s how it ended up, along with thousands of streets just like it across the country. Our streets can be fast or they can be safe. After decades of tragedy, it’s time we woke up to this fact: we can’t have it both ways.

Source: Google Street View

I have no doubt that the driver who killed this young man meant no harm, but made a mistake by either driving too fast, not paying enough attention, or both. I have no doubt that this young man was a good kid who usually looked both ways and tried to be cautious when crossing the street, but perhaps wasn’t cautious enough. Obviously, human error was at play. But the consequences for minor lapses of judgement shouldn’t be death.

This street is long, straight, and wide. Everything about this design tells the driver, “Go ahead, drive fast. It will be OK.” Meanwhile, children are crossing at a marked crosswalk, lulled into a false sense of security. As a human being, and as a teenage boy in particular, the young man who was killed here was challenged in judging the speed of oncoming cars and the risk they posed to his safety. He didn’t know it, but the odds were stacked against him. We set these kids up for failure in a big way, and we do this again and again all over the region and the country.

What’s the solution? There are numerous other “traffic calming” treatments that could be added to this street, none of which really cost that much, especially when compared to the precious young lives that are at stake. If we can afford to add new streets and highways, we can afford to fix our existing streets first. You can start with a temporary implementation in your city to spark people's imagination.

That said, the best, most lasting solution is to narrow the street until it’s uncomfortable to drive fast. There have been some previous Strong Towns posts on the virtues of narrow streets. The benefits go well beyond safety, as articulated in “Narrow Streets do More with Less,” and “Some Thoughts on Narrow Streets.”

I’m calling out my entire profession. This is a systemic issue. A tragic case of groupthink gone wrong. The change needs to come from the highest levels of leadership all the way down the chain. Just as important, change needs to come from policy makers (i.e. elected officials) who make it crystal clear that safety is more important than speed. The change needs to come from an educated public that understands this tradeoff and is OK with it. Until that happens, the tragedies will continue.

Note: This article was originally published on the Stong Towns blog.

About the author: Jon Larsen, PE works as a traffic engineer, with an emphasis on travel demand forecasting and regional transportation planning. He currently serves as the CNU-Utah Board Chair.